Death scares us in our day and age. It undoubtedly scared people just the same in the Middle Ages, but differently. Existence was perceived as an imperfect passage that led to eternal life and happiness. This obsession with death gave way to an abundance of works of art. One thousand years of history are looked into in a multi-disciplinary manner through numerous objects, works of art, documents and documentary films, from public and private collections. Organized around four themes, the exhibition is accessible to the blind and the visually impaired, who will even be allowed to touch certain objects while educational and recreational areas have been created for children.

What did man die from?

The first part looks into the causes of death in the Middle Ages. The lack of hygiene, food problems, famines, limited medical knowledge, leprosy and plague epidemics, as well as wars and the use of torture considerably affected life expectancy which at the time was much shorter than ours. Death was part of every day life. Next to a superb apothecary's sign in sculpted wood that belongs to the Musées royaux des Beaux Arts, Chronique de Gilles le Muisit, a manuscript from the XIVth century tells the story of the great plague in Tournai in 1349. A leper's rattle in polychrome wood from the Museum of Bruges indicates the life of the destitute and a baby's silver bottle from the Louvre museum in Paris illustrates infant mortality.

Accompanying the dead

Funerary rites are the second theme. Links between individuals and the community are reinforced by a series of rituals linked to the demise, the burial, mourning and the commemoratory ceremonies. We can observe major social differences in the manner in which the body is dealt with, according to the person's social position. The fate of the underprivileged pariahs (lepers, those condemned to death, Jews, non baptized children, etc.) is equally looked into. Aside from a few skeletons from the Merovingian collections of the Cinquantenaire museum, we must point out the presence of two portraits painted in the XVIth century by Bartholomeus II Bruyn (Musées royaux des Beaux-Arts of Belgium), representing a man and a woman on their death beds. Two other major items are the manuscript from Le Mans recounting the funeral of Anne de Bretagne and the lead box that held the heart of the count of Egmont, on loan exceptionally by the church of Zottegem.

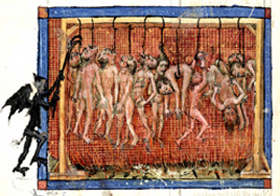

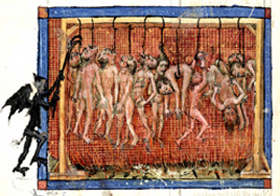

Guillaume de Digulleville. The dream of the pilgrimage of human life; Torture in Hell, Detail, Flanders, circa 1380-1390

Bibliothèque royale de Belgique, Manuscript Cabinet, Brussels, ms. 10176-8, folio 150v

The third section focuses on funerary monuments. Places of worship and cemeteries held an important place in medieval society. Mausoleums and funerary monuments contrasted with normal tombs and common graves. Sarcophagus, tombstones, funerary slabs and other recumbent statues trace the evolution of funerary traditions in the Middle Ages. The fourth and last part presents the beliefs and superstitions linked to death. Once he has died, the deceased must wait for the final judgment. According to his behavior, he will be sent to paradise, heaven, or hell. Dances of death, the wheel of fortune and the ars moriendi describe the relation to eternal life in the Christian imagination. Among the masterpieces presented there is a superb ivory memento mori from the XVIth century (Musée des Arts décoratifs in Paris) that represents a skeleton sitting on a tomb, the elbow resting on a sandglass, and a page from a manuscript from the XVth century, from a private collection, showing one of the oldest known representations of death in the form of a skeleton holding a scythe.

PUBLICATION:

Entre Paradis et Enfer - Mourir au Moyen Âge, directed by Sophie Balace, Alexandra De Poorter and Frans Verhaeghe, Fonds Mercator, Brussels, October 2010, paperback edition, 28x24 cm, 232 p. 39,5 €

To see more illustrations, click on VERSION FRANCAISE at the top

of this page

|